A lot of people eat chicken eggs every day, whether they’re boiled, scrambled, fried, or used in baking and cooking. But have you ever thought about how many cells are inside a chicken egg? It turns out that the science behind how eggs are made and how they grow is very interesting. This article will look at the complicated structure of a chicken egg and tell you how many cells are inside it.

The Basic Structure of a Chicken Egg

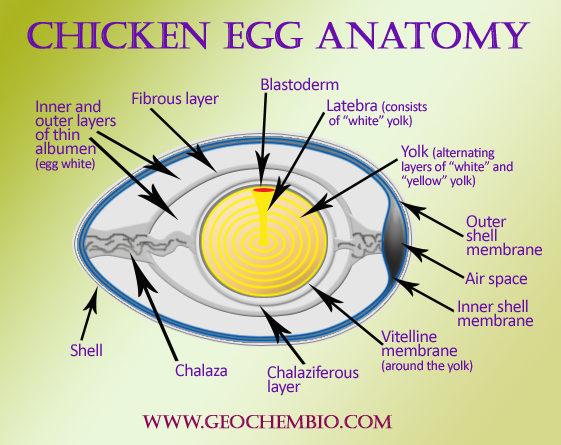

Let’s take a quick look at the different parts of a chicken egg before getting into the specifics of the cells.

-

Shell – The hard outer covering made mostly of calcium carbonate that protects the interior contents It contains thousands of tiny pores for gas exchange.

-

Shell Membranes: These are two thin protein membranes that are just under the shell and offer extra protection.

-

Albumen (Egg White) – The clear liquid surrounding the yolk, composed mainly of water and proteins.

-

Chalazae – Rope-like strands of protein anchoring the yolk in the center of the egg.

-

Yolk – The yellow spherical part containing fats, proteins and nutrients to supply the potential chick embryo.

To put it simply, a chicken egg has a shell that protects it, an egg white that is soft, and a yolk that is full of nutrients. But how do these parts relate to specific cells? Let’s look at each part separately.

Counting the Cells in the Yolk

The yolk makes up the majority of cells found inside a chicken egg. It contains numerous structures called oocytes, which are large reproductive cells that develop into chicks if fertilized. The yolk is packed with nutrients, proteins, fats and vitamins to nourish the embryo during incubation.

Research indicates a single yolk houses around 5,000 oocytes, each surrounded by support cells called granulosa cells. So just within the yolk alone, we already reach a tally of several thousand cells.

The Cellular Composition of Egg Whites

Egg whites provide additional cells, though substantially less than the thousands contained in the yolk. Studies show the albumen holds approximately 200 specialized cells.

These cells produce the major egg white proteins:

- Ovalbumin – Provides nutrition

- Ovotransferrin – Antimicrobial properties

- Ovomucin – Thick gel-like texture

- Lysozyme – Breaks down bacterial cell walls

So while minimal in number, these cells enable key functions like protecting the yolk and supplying nutrients.

Estimating Cells in the Shell Membranes

The two shell membranes are very thin but play important roles. The inner membrane is made of dense fibers to regulate gas exchange. Meanwhile, the outer membrane contains collagen for structural reinforcement.

Though not definitively quantified, estimates based on their structural composition suggest each membrane likely contains 100 to 500 cells.

Crunching the Numbers on Total Egg Cells

If we tally up the cell estimates for each part of the chicken egg, we land on an approximate range of:

- Yolk: 5,000 cells

- Egg Whites: 200 cells

- Shell Membranes: 100 to 500 cells

Therefore, the total number of cells in a single chicken egg is estimated to be 5,300 to 5,700 cells.

Of course, this number represents an average and can vary based on specific factors like egg size, hen breed and diet. Nonetheless, it illustrates the fascinating biology hidden within an everyday food.

The Specialized Cells Support Embryo Development

It’s incredible that approximately 5,000 to 6,000 cells can come together to create an environment capable of forming a complex organism.

If fertilized by a rooster, the oocytes in the yolk begin rapid division as an embryo forms. The egg white cells synthesize protective proteins while the membranes regulate optimal gas levels.

Together, these specialized cells supply the essential nutrition, defenses and ideal conditions to nurture a growing chick throughout three weeks of incubation.

The Changing Cell Count During Embryo Growth

Once the single-celled oocyte is fertilized, the cell count skyrockets from around 5,000 to trillions as the chick develops:

- 4 hours: 4 cells

- 24 hours: 50,000 cells

- 3 days: 70,000 cells

- 4 days: 1 million cells

- 10 days: 40 million cells

- 18 days: 3 billion cells

You can visualize the embryo progressing from just a tiny cluster of cells into a fully recognizable chick in a matter of days. The cells multiply exponentially, differentiating into specialized tissues and organs to create a brand new animal.

It’s mind-blowing that such an explosion of cells with distinct identities stems from the components housed in a humble chicken egg.

Key Takeaways on Cells per Egg

To recap the key details on the cellular construction of chicken eggs:

-

A single chicken egg contains approximately 5,000 to 6,000 cells total.

-

The majority reside in the yolk (around 5,000 oocytes) with a few hundred additional cells in the egg whites and membranes.

-

If fertilized, the oocytes rapidly divide from one cell into trillions as the chick embryo develops.

-

Specialized albumen and membrane cells help create optimal conditions for growth.

So the next time you crack open an egg, remember that thousands of intricately organized cells lie within!

Appreciating the Remarkable Biology of Eggs

Chicken eggs provide the perfect environment to transform a single cell into a living organism. Their wondrous biology delivers the ideal combination of nutrition, protection and microconditions to support new life.

Beyond their importance in reproduction, eggs also serve as an efficient nutrition delivery system. Their durability combined with a balanced nutrient profile made eggs a prized food source across cultures worldwide.

Whether fried, baked or boiled, each egg sitting on your breakfast plate started as a cluster of approximately 5,000 remarkable cells with the potential to create a breathing chick. If not fertilized, luckily those cells instead provide humans with an accessible dose of high-quality protein.

So as you enjoy your omelette, quiche or egg salad sandwich, take a moment to appreciate the true wonder of cells that eggs represent. Cracking the science behind this everyday food reveals intricate details of biology we often take for granted.

Eggs Develop in Stages

A developing egg is called an oocyte. Its differentiation into a mature egg (or ovum) involves a series of changes whose timing is geared to the steps of meiosis in which the germ cells go through their two final, highly specialized divisions. Oocytes have evolved special mechanisms for arresting progress through meiosis: they remain suspended in prophase I for a prolonged period while the oocyte grows in size, and in many cases they later arrest in metaphase II while awaiting fertilization (although they can arrest at various other points, depending on the species).

The specific steps of oocyte development (oogenesis) are different for each species, but the main steps are the same, as shown in Primordial germ cells migrate to the forming gonad to become oogonia, which proliferate by mitosis for a period before differentiating into primary oocytes. At this stage (usually before birth in mammals), the first meiotic division begins: the DNA replicates so that each chromosome consists of two sister chromatids, the duplicated homologous chromosomes pair along their long axes, and crossing-over occurs between nonsister chromatids of these paired chromosomes. After these events, the cell remains arrested in prophase of division I of meiosis (in a state equivalent, as we previously pointed out, to a G2 phase of a mitotic division cycle) for a period lasting from a few days to many years, depending on the species. During this long period (or, in some cases, at the onset of sexual maturity), the primary oocytes synthesize a coat and cortical granules. In the case of large nonmammalian oocytes, they also accumulate ribosomes, yolk, glycogen, lipid, and the mRNA that will later direct the synthesis of proteins required for early embryonic growth and the unfolding of the developmental program. The intense biosynthetic activities in many oocytes can be seen in the structure of the chromosomes, which loosen up and form lateral loops, giving them a unique “lampbrush” look that shows they are working hard on RNA synthesis (see and ).

The stages of oogenesis. Oogonia develop from primordial germ cells that migrate into the developing gonad early in embryogenesis. After a number of mitotic divisions, oogonia begin meiotic division I, after which they are called primary oocytes. In mammals, (more. ).

The next phase of oocyte development is called oocyte maturation. It usually does not occur until sexual maturity, when the oocyte is stimulated by hormones. Under these hormonal influences, the cell resumes its progress through division I of meiosis. The chromosomes recondense, the nuclear envelope breaks down (this is generally taken to mark the beginning of maturation), and the replicated homologous chromosomes segregate at anaphase I into two daughter nuclei, each containing half the original number of chromosomes. To end division I, the cytoplasm divides asymmetrically to produce two cells that differ greatly in size: one is a small polar body, and the other is a large secondary oocyte, the precursor of the egg. At this stage, each of the chromosomes is still composed of two sister chromatids. These chromatids don’t split until meiosis II, when they are split into two separate cells, as we’ve already talked about. After this final chromosome separation at anaphase II, the cytoplasm of the large secondary oocyte again divides asymmetrically to produce the mature egg (or ovum) and a second small polar body, each with a haploid set of single chromosomes (see ). Because of these two asymmetrical divisions of their cytoplasm, oocytes maintain their large size despite undergoing the two meiotic divisions. Both of the polar bodies are small, and they eventually degenerate.

In most vertebrates, oocyte maturation proceeds to metaphase of meiosis II and then arrests until fertilization. At ovulation, the arrested secondary oocyte is released from the ovary and undergoes a rapid maturation step that transforms it into an egg that is prepared for fertilization. If fertilization occurs, the egg is stimulated to complete meiosis.

Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition.

In one respect at least, eggs are the most remarkable of animal cells: once activated, they can give rise to a complete new individual within a matter of days or weeks. No other cell in a higher animal has this capacity. Activation is usually the consequence of fertilization—fusion of a sperm with the egg. In some organisms, however, the sperm itself is not strictly required, and an egg can be activated artificially by a variety of nonspecific chemical or physical treatments. Indeed, some organisms, including a few vertebrates such as some lizards, normally reproduce from eggs that become activated in the absence of sperm—that is, parthenogenetically.

Although an egg can give rise to every cell type in the adult organism, it is itself a highly specialized cell, uniquely equipped for the single function of generating a new individual. The cytoplasm of an egg can even reprogram a somatic cell nucleus so that the nucleus can direct the development of a new individual. That is how the famous sheep Dolly was produced. The nucleus of an unfertilized sheep egg was destroyed and replaced with the nucleus of an adult somatic cell. An electric shock was used to activate the egg, and the resulting embryo was implanted in the uterus of a surrogate mother. The resulting normal adult sheep had the genome of the donor somatic cell and was therefore a clone of the donor sheep.

In this section, we briefly consider some of the specialized features of an egg before discussing how it develops to the point of being ready for fertilization.

PARTS OF AN EGG | Parts of an Egg and their Functions | Science Lesson

FAQ

Is chicken egg 1 cell?

The eggs of most animals are giant single cells, containing stockpiles of all the materials needed for initial development of the embryo through to the stage ….

What is the number of cells in a hen’s egg?

The egg of a hen is just one cell.

How many cells are in an unfertilized egg?

A median of 2.5 cells was counted with a range of two to 20 cells.Jan 1, 2008

How many cells does an egg yolk have?

Yes, an egg yolk is a single gigantic cell. The ‘skin’ on the outside of an egg yolk is the skin that all cells have, just bigger. If you cut a yolk in half you’ll burst the skin and it’ll pop so you can’t get 2 cells out of it that way.

Is chicken egg a single cell?

The egg ( chicken egg) or any other egg is a single cell with the genome of the respective species. In humans also the Oocyte (ovum) is one of the largest single cell. Egg in birds or reptiles is a single cell which if fertilized is diploid in natureand if unfertilized or parthenogenetic is haploid. How is the chicken egg like a cell?.

Is a hen egg a cell?

The egg of a hen is a cell. It divides repeatedly and differentiates into various tissues to develop into a chicken. How is an egg cell formed?.

How many cells are in a chicken egg?

The female gamete or egg cell for most species is generally quite small, being no larger than a pencil point. Oddly enough, the large, edible egg of a chicken consists of just one single, solitary cell. Quirky! Note: You might also enjoy reading The Y-Chromosome – Is It in Danger? Have you ever wondered how many cells there are in a chicken egg?.

How many cells is an unfertilized egg composed of?

An unfertilized egg, or egg cell, is a single cell. After fertilization, it forms the single cell zygote, which then divides by the end of the first 24 hours, forming a 2-cell embryo. Usually, the timing of the first inspection of the embryos is in the morning of Day 2, and at this stage, there should be a 4-cell embryo. By Day 3, it should be a 6 to 8-cell embryo.

How a hen’s egg is a single cell structure before fertilisation?

Thus, hen’s egg is a single cell structure before the fertilisation which can be seen by naked eyes. In a chicken’s ovary, there are thousands of tiny eggs that haven’t formed yet. When they have mature eggs, one will be released into the oviduct and the formation process will begin.

Is egg a single cell?

The egg which we eat is not a single Ovum (egg cell), but an ovum with a nutrient sack (the yolk) suspended in a nutrient protein broth (the egg white). In fairness, the egg yolk is connected to the ovum, so it could be construed as one cell, but the functioning cell part is microscopic. TL;DR a little bit yes, but mostly no.